Urbanization in Africa is accompanied by improved modernization of the economy.

The share of the urban population in Africa grew from about 32% in 1990 to about 47% in 2020. Such phenomenal growth is expected to be either caused or led by a process of modernization or industrialization. Most observers and researchers suggest that urbanization in Africa has followed a rather different path where urban settlements have been characterized generally by a movement of people from agrarian subsistence framing to be employed in the equally less productive, informal sector with little industrialization taking place[1]. Part of the dynamics explaining this phenomenon is the preponderance of push factors in rural areas, such as landlessness, population pressure, conflict) than pull factors in urban areas (high remunerative job opportunities, etc). This may be true in a number of cases. But this is not also the full picture. In fact, it could be an oversimplification. This brief examines the association between urbanization and employment in the modern sector using highly dis aggregated GDP and employment data (10-sector)[2] for 11 African countries covering the period 1985-2012.

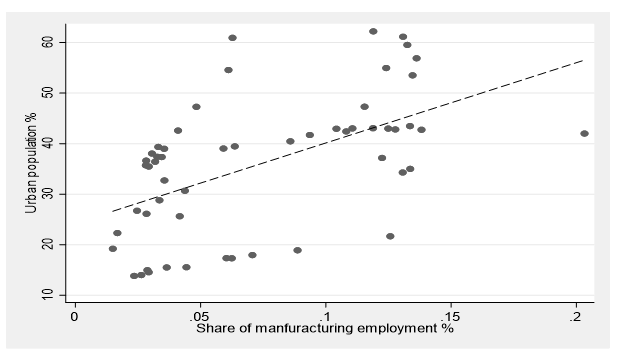

Figure 1: Urbanization and share of employment in manufacturing (%)

Note: Author’s computations based on data by Timmer et al (2015)

Figure 1 shows that during 1985-2012 urbanization in Africa was associated with high rate of employment in the manufacturing sector. This is a pattern slightly different from the established narrative that urbanization took place in Africa with little or no process of modernization in the economy. It is important to note also that there is relatively high degree of variation in the experiences of countries around the mean (linear regression line). There are countries where urbanization rate is between 30-45% yet share of employment in the manufacturing sector is less than 5% and vice versa. From Figure 1 it can also be argued that even for countries where urbanization exceeded 50%, employment in the manufacturing sector did not exceed 15%, hence compared with other regions of the world, African urbanization is still not dominated by a process of industrialization.

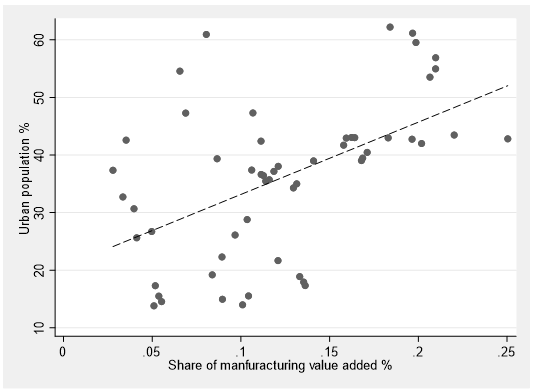

Figure 2: Share of urban population and valued added in manufacturing in Africa

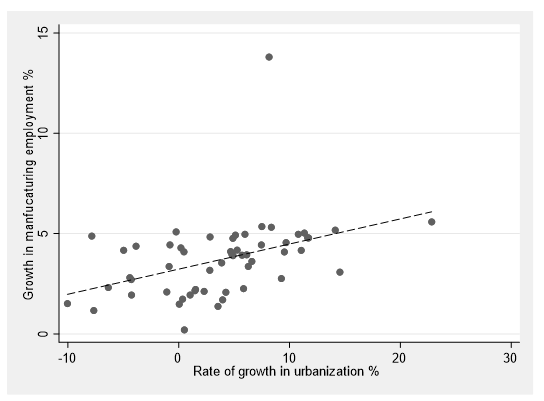

Figure 2 also illustrates similar patterns on the association between urbanization and modernization rates in Africa where the share valued added in the manufacturing sector was positively and strongly correlated with the rate of urbanization. While Figures 1 and 2 provide relationships that may be of long-term nature between urbanization and modernization of the economy, where underlying structural and institutional differences between countries could be at a play, Figure 3 presents the growth rates in urbanization and that of employment in the manufacturing sector, which underpins more of the instantaneous relationships. It is shown that countries that experienced higher pace of urbanization also experienced higher rate of growth in employment in the manufacturing sector strengthening the argument that urbanization in Africa did not take in a vacuum of economic transformation.

Figure 3: Growth in manufacturing employment and rate of urbanization in Africa

During this period, on the average urbanization grew in these countries at a pace of around 2.8% per year, while employment in the manufacturing sector grew at around 2.5%. From Figure 3 it could be inferred that a 1% growth in urbanization led to a 1.2% growth in manufacturing employment which is quite substantial.

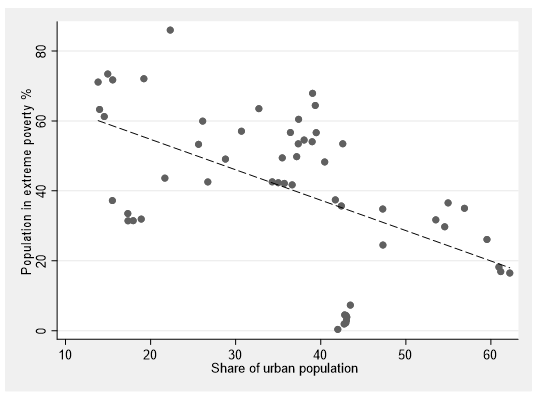

Poverty declined in countries with high rate of urbanization, but inequality also worsened

One of the positive effects of urbanization in Africa is that it has led to significant decline in the rate of poverty between countries. Hence it is conceivable to expect that the process of urbanization, particularly one that is underpinned by modernization of the economy could be important to tackle poverty in Africa. Estimate of the elasticity of poverty with respect to urbanization suggest that a 1% increase in the pace of urbanization could yield a poverty reduction rate of 1.2% per annum. Given that urbanization on the average in the countries in our sample increased at a pace of around 2.8%, we would expect poverty to decline by around 3.6% annually. It is also important to note the country variations where this reality may not happen. There are countries where urbanization rate is over 40%, yet the percentage of the population living in poverty is higher than 50%. Fleshing out the factors underpinning such heterogeneous experience becomes very important for policy purposes.

Figure 4: Extreme poverty and urbanization in Africa

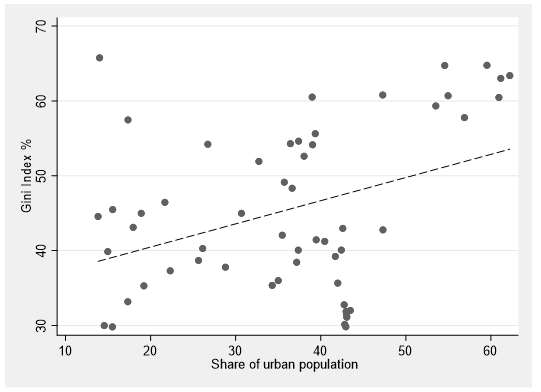

Finally, all is not rosy in the urbanization process. As Figure 5 shows it is also a process that is not equalizing. The Gini coefficient, popular measure of economic inequality suggest that it is positively correlated with rate of urbanization. Countries that have high rate of urbanization also exhibit high degree of inequality. This may not be surprising as urban economies are more differentiated and exhibit livelihoods with varying earning differentials compared with those in rural areas. As countries urbanize, they will be facing serious and persistent inequality that could be harmful for political stability and future progress in economic activities.

Figure 5: Inequality and urbanization in Africa

In summary, this brief presented a few facts about some features of urbanization in Africa. While the dominant narrative remains where still most African cities are crowded and are host to millions of people surviving on minimum earnings or wages mostly in the informal services sector, there has been also a positive trend that has been little noticed taking place. One of these is that manufacturing employment, both in levels and rate of growth has been positively correlated with the pace of urbanization. In addition, countries that tended to have high urbanization rates also exhibited low poverty rates. We have also noticed that some of the most urbanized countries (with urbanization rates above 50%) exhibited inequality levels that are pervasive reaching more than 40% and in some cases above 60% rendering the prospect of urbanization to be un-equalizing in the development process. There is some hope when it comes to poverty and inequality in the urbanization process. The relationship does not hold when growth rates are taken, indicating that the pattern documented in Figure 4 and 5 is more of a long-term relationship driven by structural and institutional factors prevailing in the continent. More research is needed to drill down how public policies could shape the urbanization process to become friendly to inclusive growth going forward.

[1] E.g see Potts, D. “Challenging the Myths of Urban Dynamics in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Evidence from Nigeria”, World Development” vol 40, no 7, pp 382–1393,

[2] The data source is Timmer, M. P., de Vries, G. J., & de Vries, K. (2015). “Patterns of Structural Change in Developing Countries.” . In J. Weiss, & M. Tribe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Industry and Development. (pp. 65-83). Routledge.

- The ageing population of Africa is increasing, so it’s suffering - October 10, 2021

- Are social protection programs effective in caring for the elderly in Africa? - October 5, 2021

- For whom the bell tolls? Social Protection in Africa during Covid-19 pandemic - September 30, 2021